The Intersection of Nature and Engineering in Central Florida

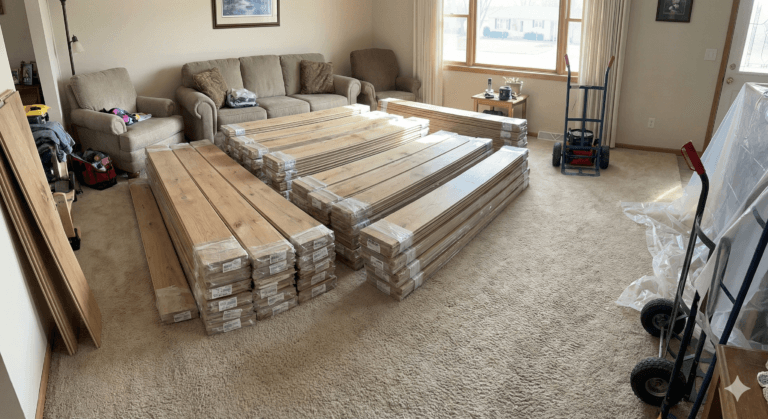

The selection of flooring is far more than a decorative choice; it is a foundational investment in the structural integrity, acoustic comfort, and long-term asset value of a home. For homeowners in Central Florida, this decision is further complicated by a unique and challenging environmental context. The region’s subtropical climate, characterized by high ambient humidity, heavy rainfall, and the prevalence of concrete slab-on-grade foundations, creates a specific set of stressors that can compromise traditional flooring materials. In this demanding landscape, engineered wood flooring has emerged not merely as an alternative to solid hardwood, but as the technically superior solution, bridging the gap between the aesthetic desire for organic luxury and the physical necessities of the Florida environment.

This comprehensive guide serves as an exhaustive resource for homeowners, dissecting the complexities of engineered wood flooring. It moves beyond superficial marketing claims to analyze the structural anatomy of high-performance planks, the critical chemistry of moisture-barrier adhesives, and the financial realities of installation in the Tampa and Orlando markets. By equipping homeowners with deep technical knowledge—translated into accessible concepts—this report aims to build the confidence necessary to make an informed, lasting investment. It is designed to be the definitive “owner’s manual” for navigating the selection, installation, and maintenance of wood floors in a humid climate.

The Shift from Solid to Engineered

Historically, solid hardwood was the gold standard. A single piece of timber, milled from top to bottom, offered purity and tradition. However, wood is hygroscopic—it acts like a sponge, absorbing and releasing moisture to reach equilibrium with its environment. In the dry climates of the American Southwest or the climate-controlled basements of the Northeast, solid wood performs admirably. In Central Florida, however, the “sponge” effect is catastrophic. A 5-inch wide plank of solid Oak can expand significantly across its width when exposed to the moisture vapor constantly migrating up through a concrete slab or infiltrating from the humid outdoor air.

This physical limitation drove the innovation of engineered wood flooring. By reconfiguring the internal structure of the plank while preserving the top layer of genuine hardwood, manufacturers created a product that is up to 700% more dimensionally stable than its solid counterpart. This stability allows for the installation of wider, longer planks—now the dominant trend in interior design—without the risk of cupping, buckling, or gapping that plagues solid wood in humid zones. Understanding this fundamental shift is the first step in appreciating why engineered wood is the logical choice for the Florida homeowner.

1: The Anatomy of a High-Performance Plank

To the untrained eye, an installed engineered wood floor is indistinguishable from a solid hardwood floor. Both present a surface of genuine timber, boasting the natural grain patterns, knots, mineral streaks, and chromatic variations that characterize organic materials. However, the similarities end at the surface. The internal architecture of an engineered plank is a feat of industrial design intended to overcome the natural hydroscopic limitations of solid lumber. Understanding this anatomy is critical for distinguishing between a “budget” product that will fail in five years and a “legacy” product that will last for generations.

1.1 The Wear Layer (The Lamella)

The topmost layer, known technically as the lamella or wear layer, is the defining component of the floor’s aesthetic and longevity. This is the slice of actual hardwood—Oak, Maple, Hickory, Walnut, or exotic species—that is visible and walked upon. The method of its production and its thickness are the primary drivers of cost and durability.

Production Methods: Sawn vs. Rotary Peeling

Not all wear layers are created equal. The method used to harvest the wood from the log drastically affects the look and performance of the floor.

- Dry Sawn Face: This is the premium standard. The lumber is cut from the log in the same manner as solid planks.

- Aesthetic: It preserves the natural grain structure, looking exactly like solid wood. It captures the “cathedrals” and linear grain patterns inherent to the species.

- Performance: Because the wood fibers are not stressed during cutting, sawn veneers are more dimensionally stable.

- Market Position: Found in mid-to-high-end products ($8.00+ per sq. ft.).

- Sliced Veneer: Similar to sawn, but the wood is sliced with a blade rather than cut with a saw.

- Aesthetic: Still retains a natural look but can sometimes develop fine cracks (checking) if the slicing process stressed the wood fibers.

- Performance: Slightly less stable than sawn but more cost-effective.

- Rotary Peeled: The log is spun against a sharp blade, peeling off a continuous sheet of wood like a roll of paper towels.

- Aesthetic: This produces a chaotic, wide, and repetitive grain pattern that often looks like plywood. It lacks the natural look of traditional lumber.

- Performance: The peeling process puts immense tension on the wood fibers, making these veneers more prone to cupping and checking in humid environments.

- Market Position: Found in entry-level and budget products (<$5.00 per sq. ft.).

The Thickness Equation: Longevity Defined

The thickness of the wear layer is the most accurate predictor of the floor’s lifespan. It determines how many times the floor can be sanded and refinished—a critical maintenance capability for a long-term investment.

- Entry-Level (0.6mm – 2mm):

- Reality: These floors are essentially “disposable” in the context of real estate assets. A wear layer this thin cannot be sanded. If a deep scratch occurs, it may penetrate through the color or even the wood itself, exposing the core material.

- Refinishing Potential: Zero. Once the finish wears out, the floor must be replaced or recoated with extreme caution.

- Use Case: House flipping, low-traffic guest rooms, or budget-constrained renovations where longevity is not a priority.

- Mid-Range (2mm – 3mm):

- Reality: This is the “sweet spot” for many homeowners. A 3mm wear layer provides the look and feel of solid wood and offers significant durability.

- Refinishing Potential: Limited. A 2mm layer cannot be sanded, but it can be “screened and recoated” (a process of abrading the top finish and applying a new coat of polyurethane). A 3mm layer might handle one very careful professional sanding, but the risk of sanding through to the core is high.

- Use Case: Standard residential use. It balances cost with a 15-25 year service life.

- Heirloom Quality (4mm – 6mm):

- Reality: These products are functionally equivalent to solid wood in terms of wear. The “wearable” amount of wood on a solid plank (the wood above the tongue and groove) is typically about 6mm. Therefore, an engineered floor with a 6mm wear layer has the same usable life as a solid floor.

- Refinishing Potential: High. These floors can be fully sanded and refinished 3 to 5 times.

- Use Case: Luxury homes, “forever” homes, and high-traffic areas. Expected lifespan: 40-80+ years.

Insight for Florida Homeowners: In a market where real estate values are climbing, installing a product with a <2mm wear layer can actually be a detriment to resale value, as savvy buyers recognize it as a temporary finish. A 3mm or 4mm wear layer represents a robust investment that signals quality to future buyers.

1.2 Core Construction Architectures

Beneath the glamour of the wear layer lies the core—the structural engine of the plank. This section is responsible for the product’s dimensional stability and its ability to resist the aggressive humidity of the Florida peninsula.

The Multi-Ply Plywood Core

The most common and generally preferred core for humid climates consists of multiple thin layers (plies) of wood, typically Birch or Eucalyptus.

- The Cross-Grain Mechanism: The genius of this design lies in the orientation. Each ply is glued with its grain running 90 degrees perpendicular to the layers above and below it. Wood naturally expands across its grain width. By bonding layers in alternating directions, the layers physically restrict each other’s movement. If the top layer tries to expand width-wise due to humidity, the layer beneath it (running length-wise) acts as a structural anchor, resisting that movement.

- Quality Indicators:

- Layer Count: Higher quality cores have more plies (7 to 11 layers) rather than fewer (3 to 5). More layers create a stiffer, more stable board.

- Species: Premium cores use Baltic Birch for all layers. Budget cores may use softer woods like Poplar or mixed species, which have less holding power for fasteners and are less stable.

High-Density Fiberboard (HDF) Core

HDF cores are composed of wood fibers compressed with resin under extreme pressure.

- Advantages: HDF is significantly harder than plywood, offering superior dent resistance. It is also extremely uniform, allowing for incredibly precise milling of “click-lock” mechanisms used in floating floors.

- The Moisture Risk: Standard HDF acts like a sponge if water penetrates the joints. It swells and, unlike wood, does not shrink back to its original shape when dry. While “moisture-resistant” HDF resins exist, they are generally riskier for glue-down applications on concrete slabs in Florida compared to marine-grade plywood.

Finger-Core / Blockboard

This core uses small blocks of solid wood (often Spruce or Pine) arranged perpendicular to the veneer.

- Characteristics: It provides the heft and sound of solid wood. However, a phenomenon known as “telegraphing” can occur, where the pattern of the internal blocks becomes visible on the surface over time as the blocks expand and contract at different rates than the veneer. This is often found in mid-tier imports.

1.3 The Backing Layer

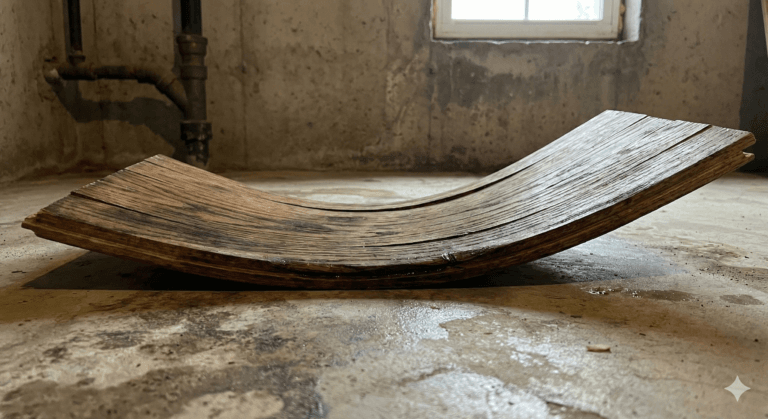

The unsung hero of the plank is the backing layer. In high-quality “balanced construction,” the backing layer is made of the same species or a species with similar density to the top wear layer. This ensures that the tension exerted by the top layer is equalized by the bottom layer, keeping the plank flat. Cheaper productions may use a generic softwood backing, which can lead to bowing (the plank curving like a banana) before it even leaves the box.

2: The Florida Factor – Humidity, Concrete, and Hydrostatic Pressure

Central Florida presents a hostile operational theater for wood flooring. The combination of a high water table, high ambient humidity, and the ubiquity of slab-on-grade construction creates a “moisture sandwich”—humidity attacking from the air above and vapor pressure pushing from the concrete below.

2.1 The Concrete Slab Challenge

In regions like the Northeast, floors are often installed over wood subfloors with basements, allowing for nail-down installation. In Tampa, Orlando, and surrounding areas, the subfloor is almost universally concrete.

- Moisture Vapor Transmission (MVT): Concrete is porous. Even significantly cured slabs can transmit moisture vapor from the damp ground into the home. This invisible vapor pressure can accumulate under a wood floor. If the pressure exceeds the adhesive’s tolerance, it can cause the glue to release (adhesive failure) or the wood to swell and buckle.

- Alkalinity: As moisture moves through concrete, it dissolves salts and brings them to the surface, raising the pH level. High alkalinity can chemically degrade certain adhesives over time, turning strong glue into a brittle, useless substance.

The “Floating” vs. “Glued” Debate: The “floating” installation method is often marketed as a solution to concrete moisture because it separates the wood from the slab with a plastic sheet. However, this creates a “hollow” sound and feel that many homeowners find creates a lower-value perception compared to the solid, permanent feel of a glue-down floor. The industry best practice for luxury homes in Florida is a glue-down installation using a specialized moisture-barrier adhesive.

2.2 Ambient Humidity and The Myth of Acclimation

Wood is hygroscopic; it constantly absorbs and releases moisture to reach equilibrium with its environment.

- Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC): In Florida, the average indoor EMC is higher (12-13%) than in drier states like Nevada (4-7%).

- The Acclimation Myth: A dangerous misconception is that wood simply needs to sit in a house for a few days to be “ready.” However, if the house is under construction and the Air Conditioning (HVAC) is not running, acclimating the wood to the hot, humid construction site is detrimental. The wood will absorb that excess humidity, swell, and then shrink dramatically once the homeowner moves in and turns on the AC, resulting in massive gaps between boards.

- The Correct Protocol: The wood must be acclimated to living conditions. This means the HVAC system must be operational for at least 5 days prior to the wood delivery. The wood must then sit in that conditioned air (with boxes opened or stacked to allow airflow) for 48-72 hours minimum. The goal is to install the wood at the same moisture level it will maintain for the rest of its life.

2.3 Why Solid Wood Fails Here

Solid hardwood is highly reactive. A 5-inch wide solid plank of Oak can expand by a measurable fraction of an inch across its width with a small increase in moisture content. In Florida, this movement creates immense pressure.

- Cupping: The bottom of the board (near the moist concrete) expands more than the top (dried by the AC), causing the edges of the board to curl upward, creating a “washboard” effect.

- Buckling: In extreme cases, the expansion force is so great that the wood rips away from the subfloor, lifting inches into the air.

- The Engineered Advantage: The cross-ply construction reduces this expansion/contraction coefficient by up to 700% compared to solid wood. This stability is the only reason why 7-inch, 9-inch, or even 12-inch wide planks—which are aesthetically trending—are physically possible in Florida homes.

3: Selecting the Right Floor – Aesthetics Meets Physics

Selecting the right product involves balancing visual preference with physical durability (Hardness) and chemical safety.

3.1 Wood Species and Hardness (Janka Scale)

The Janka Hardness Scale measures the force required to embed a steel ball halfway into the wood. While the engineered core provides structural stability, the species of the top veneer determines the floor’s resistance to surface indentation (dents from high heels, dropped objects, or pet claws).

| Species | Janka Rating (approx.) | Suitability for Florida / High Traffic | Characteristics & Florida Context |

| Hickory | 1820 | Excellent | The hardest domestic North American species. It features high color variation (blonde sapwood to dark heartwood). Its dense grain and hardness make it incredibly resistant to the wear and tear of sandy Florida soil tracked indoors. |

| Maple | 1450 | Good | Very hard but has a smooth, subtle grain. Because it lacks strong grain texture, scratches show more easily (like on a black car vs a white car). Light colors can yellow with intense Florida UV exposure. |

| White Oak | 1360 | Excellent | The current industry standard. It takes stain exceptionally well, offering unlimited color options. While softer than Hickory, its strong grain pattern hides wear effectively. Ideally suited for humid climates due to closed tyloses in its cellular structure, making it more water-resistant than Red Oak. |

| Red Oak | 1290 | Very Good | Traditional aesthetic with pinkish undertones. Slightly softer than White Oak. Its open grain structure hides dust and dents well, but it is more porous. |

| Walnut | 1010 | Fair | A luxury species known for deep, rich colors. However, it is significantly softer. It will dent easily from high heels or large dog claws. Best reserved for low-traffic areas or homes without large pets. |

| Birch | 1260 | Good | Similar to Maple in appearance but often softer. Frequently used in budget-friendly engineered options. |

Expert Insight: For a Central Florida household with large dogs or active children, Hickory or White Oak with a wire-brushed texture is the optimal choice. The wire-brushing process removes the softer springwood fibers, leaving a textured surface that physically hides new scratches and dents far better than a smooth, high-gloss finish.

3.2 Plank Width and Visual Space

Current interior design trends in the “Sun Belt” favor wide planks (7 inches to 10 inches) and long lengths.

- Visual Impact: Wider planks reduce the number of seams in a room, making the space feel larger, more open, and less cluttered. This complements the open-floor plans common in Florida architecture.

- The Engineering Requirement: As plank width increases, the mechanical leverage of expansion forces increases. Therefore, the wider the plank, the more critical the quality of the engineered core becomes. For planks wider than 5 inches, a high-quality multi-ply plywood core is non-negotiable to prevent cupping. Cheap cores in wide planks are a recipe for failure.

3.3 Finishes: Durability vs. Repairability

The finish is the chemical shield protecting the wood.

- Aluminum Oxide (Prefinished): The hardest finish available. Manufacturers cure urethane mixed with microscopic aluminum oxide particles under UV lights. It creates a ceramic-like shell that is incredibly resistant to scratches.

- Pro: Zero maintenance, extreme durability.

- Con: It is very difficult to spot-repair. A deep scratch often creates a white line in the finish that cannot be buffed out; it often requires replacing the board.

- Oil / Hardwax Oil: The finish penetrates into the wood rather than sitting on top. It offers a natural, matte, organic look.

- Pro: Easy to spot repair; homeowners can simply rub new oil into a scratch to blend it away.

- Con: Requires more regular maintenance and replenishment of the oil. It is less resistant to chemical spills.

4: Installation Methodologies in Central Florida

The method of installation is as critical as the product itself. In Central Florida, the interface between the wood and the concrete slab is the point of highest failure risk.

4.1 Glue-Down Installation (The Gold Standard)

In this method, the planks are adhered directly to the concrete using a high-strength adhesive.

- Pros: Solid sound and feel (no clicking or hollowness). The floor feels permanent and substantial, adding to the property’s perceived value. Adhesives can act as a monolithic moisture vapor barrier.

- Cons: Higher cost due to expensive adhesives and increased labor time. Permanent; difficult to remove later.

The Chemistry of Adhesives:

For Florida slabs, standard “bucket glue” is insufficient. Installers must use Urethane or Modified Silane (MS) Polymer adhesives that offer integrated moisture control.

- Bostik’s Best / GreenForce: These are urethane adhesives containing elastomeric properties. They allow the wood to move slightly (expand/contract) without breaking the bond to the concrete (“memory”). They also contain moisture inhibitors that block vapor transmission from the slab.

- Wakol MS 260: An MS Polymer adhesive. It is often preferred by installers because it is easier to clean off the surface of the wood if spilled (urethane is notoriously difficult to remove once cured). It offers zero VOCs and high tensile strength.

4.2 Floating Installation

The planks are glued or clicked together at the edges and rest on top of a foam underlayment, “floating” above the subfloor without being attached to it.

- Pros: Cheaper (less labor, no expensive glue). The underlayment acts as a built-in moisture barrier. Easier to repair or replace.

- Cons: Can sound hollow when walked on. “Deflection” (movement) can occur if the subfloor isn’t perfectly flat, leading to a “bouncy” feel. Less value-add for resale compared to glued floors.

4.3 Condo Specifics: Sound Control

For homeowners in condos (e.g., downtown Orlando or Tampa high-rises), Homeowners Associations (HOAs) strictly regulate sound transmission between floors.

- IIC (Impact Insulation Class): Measures the sound of footsteps or dropping objects.

- STC (Sound Transmission Class): Measures airborne sound (voices, TV).

- Requirement: Most HOAs require an underlayment with IIC/STC ratings of 50-70.

- Solution: Cork underlayment or specialized rubber/foam acoustic mats (e.g., WhisperMat, Roberts AirGuard) must be used. In a glue-down scenario, this often involves a “double-stick” method (glue the mat to the slab, then glue the wood to the mat) or using an adhesive with built-in sound dampening properties.

4.4 Subfloor Preparation: The Hidden Variable

A wood floor is only as good as the subfloor beneath it. In Florida, when removing old tile, the concrete is often left scarred, pitted, or with ridges of old mortar.

- Flatness Standard: The industry standard is that the subfloor must be flat to within 1/8th of an inch over a 10-foot radius.

- The Process: High spots must be ground down with concrete grinders. Low spots must be filled with a cementitious self-leveling compound. Skipping this step leads to hollow spots (where the glue doesn’t touch the wood) or popping noises in floating floors.

5: Comprehensive Cost Analysis (Central Florida Market 2025/2026)

The cost of installing engineered wood floors in Central Florida varies significantly based on material quality, preparation requirements, and labor complexity. Homeowners often focus solely on the “price per square foot” of the wood, neglecting the substantial costs of preparation and installation materials. The following analysis breaks down the total project cost for the 2025/2026 market.

5.1 Demolition and Preparation (The Budget Killer)

Before new floors can be installed, the old ones must go. In Florida, removing ceramic tile—which is glued directly to the concrete—is a major, labor-intensive expense.

- Tile Removal: This is loud, dusty, and heavy work. Costs range from $2.00 to $7.00 per sq. ft. depending on access and whether dustless equipment is used.

- Leveling: After tile removal, the concrete is rarely flat. Self-leveling compound and grinding labor can add $1.00 – $3.00 per sq. ft. depending on the severity of the unevenness.

5.2 Material Price Tiers

- Budget Tier ($4.00 – $7.00 / sq. ft.): Thin wear layer (<2mm), shorter plank lengths (random lengths 12″-48″), HDF or softwood core. Often rotary peeled veneer. Suitable for flips or low-traffic rentals.

- Mid-Range Tier ($7.00 – $12.00 / sq. ft.): 2mm-3mm sawn wear layer, stable plywood core, longer lengths (up to 72″). Standard White Oak or Hickory species. This is the most common choice for homeowners seeking value and performance.

- Luxury Tier ($13.00 – $20.00+ / sq. ft.): Thick wear layer (4mm-6mm), ultra-wide planks (9″+), premium finishes (reactive stain, fuming), high-grade Baltic Birch core. Often European imports. These floors are indistinguishable from the finest solid wood.

5.3 Labor and Installation Costs

Installation labor in the Tampa/Orlando area generally runs $3.50 – $8.00 per sq. ft..

- Glue-Down: Higher end of the range ($5.00 – $8.00) due to the complexity and mess of troweling glue.

- Floating: Lower end ($3.50 – $5.00).

- Adhesives: A 5-gallon bucket of premium moisture-barrier adhesive (e.g., Bostik’s Best) costs $250 – $400 and covers approximately 150-200 sq. ft.. This adds roughly $1.50 – $2.50 per sq. ft. to the material cost—a significant line item often overlooked in initial budgeting.

5.4 Central Florida Price Table (Estimated Total Project Cost Per Square Foot)

The following table estimates the total cost per square foot for a glue-down installation on a concrete slab, which is the recommended method for longevity in Florida.

| Cost Component | Budget Option | Mid-Range Option | Luxury Option |

| Engineered Wood Material | $4.50 | $8.50 | $16.00 |

| Adhesive / Moisture Barrier | $1.50 | $2.00 | $2.50 |

| Installation Labor | $3.50 | $5.00 | $7.50 |

| Demolition (Carpet) | $1.00 | $1.00 | $1.00 |

| Demolition (Tile) if applicable | ($3.50) | ($4.50) | ($6.00) |

| Subfloor Prep / Leveling | $0.50 | $1.50 | $3.00 |

| Moldings & Transitions | $0.50 | $0.75 | $1.50 |

| Total (w/ Carpet Removal) | $11.50 | $18.75 | $31.50 |

| Total (w/ Tile Removal) | $14.00 | $22.25 | $36.50 |

Note: Demolition costs are mutually exclusive; use the row that applies to your current floor. Tile removal replaces carpet removal in the total calculation.

Scenario: For a 1,000 sq. ft. living area in Orlando, replacing old tile with a high-quality Mid-Range engineered White Oak floor:

- Low Estimate: ~$18,000

- High Estimate: ~$25,000

- Timeframe: 7-14 days (including demo, prep, and acclimation).

6: Maintenance and Longevity in a Humid Climate

Maintaining engineered wood in Florida requires a departure from traditional “mop and bucket” cleaning. The goal is to minimize moisture exposure while managing the abrasive effects of sand.

6.1 The “No Water” Rule

Water is the enemy. Wet mopping can force water into the seams between boards. Even with moisture-resistant cores, the top veneer can swell at the edges, leading to finish checking (cracking).

- Protocol: Use a microfiber dust mop daily. Florida soil is sandy; tracked-in sand acts like 60-grit sandpaper, wearing down the finish rapidly if not removed.

- Cleaning Agents: Use pH-neutral cleaners specifically designed for wood floors (e.g., Bona, Basic Coatings). Avoid “oil soaps,” “polishes,” or “refreshers” (like Murphy’s Oil Soap) which leave a wax or oily residue. This residue attracts dirt and creates a film that prevents future recoating.

6.2 Humidity Control

Homeowners must treat their wood floor like fine furniture or a piano.

- Ideal Range: Maintain indoor relative humidity between 35% and 55%.

- The Vacation Home Risk: A common issue in Florida involves “Snowbirds” who leave for the summer and turn off their AC to save money. The humidity inside the closed home can spike to 80-90%, causing the floors to absorb moisture and buckle. It is imperative to leave the AC system running with a humidistat set to keep humidity below 60%, or install a whole-home dehumidifier.

6.3 Scratch Repair

- Surface Scratches: In the clear coat only. These can often be hidden with a “stain marker” or repair kit.

- Deep Scratches: Penetrating the wood. With an oil finish, apply more oil. With a urethane finish, a professional board replacement (cutting out the damaged board and gluing in a new one) is often the best solution for engineered floors that cannot be sanded.

7: Trustable Brands and Vetting Contractors

7.1 Brands with a Proven Track Record

Based on core stability, adhesive quality, and wear layer thickness, the following brands are noted for performance in variable climates like Florida :

- High-End / Boutique: Mirage (Canada), Lauzon (Canada). These manufacturers use high-grade plywood cores and sawn veneers. Their finishes are exceptionally clear and durable.

- Mid-Range / Reliable: Mannington (Latitude Collection), Shaw (Repel series – water resistant features), Mohawk (TecWood).

- Value / Performance: Bruce and Robbins (HydroGuard lines specifically target water resistance).

7.2 The Contractor Vetting Checklist

The best product will fail with poor installation. Homeowners should ask these specific questions to vet potential installers:

- “Do you perform moisture testing on the concrete slab?”

- Correct Answer: “Yes, we use Calcium Chloride tests or In-Situ Probes (ASTM F2170) to determine the moisture emission rate.” If they say “we just look at it” or “it looks dry,” do not hire them.

- “What specific adhesive do you use?”

- Correct Answer: A specific urethane or polymer brand (Bostik, Wakol, Sika) that includes moisture vapor protection. If they say “standard glue,” it’s a red flag.

- “How do you handle acclimation?”

- Correct Answer: “We deliver the wood 3-5 days early and require the AC to be running.”

- “How do you flatten the subfloor?”

- Correct Answer: “We grind high spots and use cementitious leveling compound for low spots.” If they imply they will just add more glue to fill the gaps, walk away.

Conclusion

For the Central Florida homeowner, engineered wood flooring is not a compromise; it is an upgrade in technical performance. It delivers the aesthetic prestige and emotional warmth of hardwood while navigating the treacherous hydroscopic environment of humid air and moist concrete slabs.

The key to a successful investment lies in the “invisible” details: a thick sawn wear layer (3mm+), a high-ply Baltic Birch core, a premium moisture-barrier adhesive (like Bostik’s Best or Wakol MS 260), and a rigorous acclimation process. While the upfront cost—likely between $18 and $25 per square foot for a quality turn-key installation—is significant, the result is a floor that increases home value, withstands the rigors of the tropical climate, and avoids the catastrophic warping common with solid wood.

By prioritizing construction quality over low price and ensuring installation protocols are strictly followed, homeowners can secure a foundation for their home that is as durable as it is beautiful—an investment that will stand the test of time, humidity, and trends.