The Invisible Foundation of the Florida Home

For the homeowner in Central Florida, the battle against the elements is not merely fought at the storm shutters during hurricane season, but in the microscopic pores of the materials that constitute their sanctuary. From the engineered hardwood floors of a sprawling estate in FishHawk Ranch to the custom maple cabinetry of a new build in Riverview, the structural and aesthetic integrity of a home relies heavily on a largely invisible, often misunderstood process: Material Acclimation.

This comprehensive report serves as an exhaustive guide for homeowners, dissecting the complex, symbiotic relationship between air conditioning, humidity control, and the physical stability of building materials. It challenges prevalent myths—such as the dangerous simplification that “acclimation is just waiting 48 hours”—and replaces them with science-backed truths about Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC), thermodynamics, and the specific hygroscopic behaviors of tropical construction.

We analyze the catastrophic effects of improper environmental control, including the “cupping” of expensive oak floors, the “blooming” of high-end cabinet finishes, and the structural “popping” of drywall fasteners that plague new construction. Furthermore, this report provides a localized market analysis for the Tampa Bay area, detailing the economic realities of prevention versus the exorbitant price of cure. It offers a strategic roadmap for integrating whole-home dehumidification and smart climate control into the modern Florida home, ensuring that the investment made in renovation translates into lasting value rather than costly repairs.

1: The Physics of the Home Environment

1.1 The Hygroscopic Nature of Construction

To understand why a floor buckles or a cabinet door refuses to close, one must first understand the fundamental nature of the materials used in residential construction. The vast majority of finishes inside a home—wood, drywall, concrete, and even certain paints—are hygroscopic. This means they possess the ability to attract and hold water molecules from the surrounding environment. They are, in essence, rigid sponges.

This interaction is not passive; it is a dynamic, continuous exchange of energy and mass. When a hygroscopic material is placed in an environment, it seeks thermodynamic equilibrium with the air around it.

- Adsorption: If the ambient air contains a higher concentration of water vapor (high relative humidity) than the material, the material adsorbs moisture into its cellular structure. In wood, this water occupies the spaces within the cell walls (bound water) and, upon saturation, the cell cavities (free water). This influx of mass causes the material to expand across its grain.

- Desorption: Conversely, if the air is drier than the material, the material releases moisture into the atmosphere to balance the vapor pressure. As water leaves the cell walls, the fibers draw closer together, resulting in physical shrinkage.

True acclimation is defined not by a passage of time, but by the achievement of this balance, known as Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC). A material is acclimated only when it has stopped gaining or losing moisture because it has reached a stasis with the living conditions of the home. This distinction is critical and often overlooked: acclimating flooring in a garage (an unconditioned space) prepares the wood for life in a garage, not for life in an air-conditioned living room. Installing such wood into a cool, dry interior results in immediate, often destructive, desorption.

1.2 Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC): The Governing Law

The stability of any hygroscopic material is governed by the EMC, which is a function of two variables: the Relative Humidity (RH) of the air and the Temperature of the air. In the unique climate of Central Florida, where outdoor relative humidity frequently hovers between 70% and 90% while indoor environments are mechanically cooled to 50%, the disparity between “outdoor EMC” and “indoor EMC” is extreme.

For example, a plank of White Oak stored in a warehouse in Tampa with no climate control (approx. 75% RH) will stabilize at a moisture content of roughly 14%. If that plank is installed immediately into a home in Brandon kept at 75°F and 45% RH (where the target EMC is approximately 8.5%), the wood must lose nearly 6% of its weight in water to reach equilibrium. This loss manifests as significant shrinkage. If the plank is 5 inches wide, a 6% change in moisture content can result in a shrinkage of nearly 1/16th of an inch per board. Across a 20-foot wide room, this accumulates to over 2 inches of gaps.

Conversely, consider kiln-dried cabinetry delivered at 6% moisture content. If installed in a new construction home in Riverview where the AC is not yet running and the wet trades (painting, drywall mudding) are active, the indoor humidity can spike to 80% or higher. The cabinetry will rapidly adsorb moisture, swelling at the joints. When the homeowners eventually move in and turn on the AC, the rapid drying causes the finish to crack at the joints—a phenomenon known as “bridging” failure.

1.3 The “Swamp” Factor: Florida’s Latent Load Challenge

Central Florida presents a hostile environment for building materials, distinct even from other warm climates like Arizona or Southern California. The region operates under a massive “latent load.” In HVAC terminology, “sensible load” refers to the energy required to lower the temperature of the air, while “latent load” refers to the energy required to change the state of water vapor into liquid to remove it from the air.

In a dry climate, an air conditioner primarily fights sensible heat. In Tampa Bay, the AC must fight both heat and a tremendous amount of water vapor. This “swamp factor” means that the margin for error in material acclimation is near zero. A window left open overnight during a flooring installation in Phoenix might be negligible; in Florida, it introduces enough moisture to saturate the subfloor and ruin the project.

The implication for the homeowner is that the HVAC system is not merely a comfort device; it is a structural preservation system. The air conditioner is the engine of acclimation. Without it, the home reverts to the ambient conditions of the swamp, an environment hostile to the dimensional stability of refined interior finishes.

2: The Myth vs. The Truth in Acclimation

The residential construction and renovation industry is rife with “rules of thumb” and folkloric practices that often masquerade as professional standards. When it comes to acclimation and air conditioning, these myths are not just incorrect; they are expensive.

Myth 1: “The 48-Hour Rule”

The Myth: Perhaps the most pervasive and damaging belief is that acclimation is a timed event. Contractors, eager to maintain a schedule, will often state, “The wood has been sitting here for three days (72 hours), so it is ready to install.” The Truth: Wood cannot tell time. It does not know when 72 hours have passed. It only reacts to moisture gradients. Acclimation is a rate-dependent process determined by the density of the species, the thickness of the plank, the type of finish, and the airflow around the material.

Thicker planks, denser exotic woods (like Brazilian Cherry or Teak), or materials with heavy factory finishes take significantly longer to reach equilibrium than thin, porous materials. A 3/4-inch solid hickory plank might take weeks to fully acclimate if the humidity difference between the warehouse and the home is extreme. Relying on a stopwatch instead of a calibrated moisture meter is the primary cause of flooring failure. The only metric that matters is the moisture content percentage difference between the flooring and the subfloor.

Myth 2: “Engineered Wood is Bulletproof”

The Myth: Homeowners are often upsold on engineered hardwood (a top veneer of real wood glued to layers of plywood or HDF) as a solution that is immune to humidity and requires no acclimation. The Truth: While engineered wood is dimensionally more stable than solid wood due to its cross-ply construction, it is not inert. It is still composed of cellulosic materials. In Florida’s high humidity, engineered floors can suffer from distinct failure modes, such as “shear” failure. This occurs when the top veneer expands at a different rate than the core layers, leading to delamination or checking (cracks in the veneer).

Acclimation is just as vital for engineered products. In fact, some manufacturers of high-end engineered floors explicitly require that the boxes remain sealed during acclimation to prevent the long planks from warping before installation, while others require opening the ends. The “myth” of immunity leads to negligence, which leads to failure.

Myth 3: “Turn Off the AC During Renovation”

The Myth: Homeowners and contractors often turn off the HVAC system during dusty phases of renovation—such as drywall sanding or tile demolition—to prevent dust from clogging the expensive air handler coils and filters.

The Truth: This is arguably the most dangerous practice in the Florida market. While dust control is important, turning off the AC removes the only mechanism for moisture removal in the house during a time when moisture is often being added (via paint, grout, and open doors).

- The Greenhouse Effect: A home under renovation is a moisture trap. Wet materials release gallons of water vapor. Without AC, indoor humidity spikes rapidly, often exceeding 80% or 90%.

- The Consequence: Existing cabinetry, doors, and trim absorb this excess moisture. New flooring delivered to this environment adsorbs moisture. When the renovation is complete and the AC is finally turned back on, the rapid “dry out” shocks the materials. Cabinets crack, floors gap, and drywall seams pop.

- The Solution: The HVAC system must remain running to maintain a stable EMC. The cost of changing air filters daily (or using pre-filters) is negligible compared to the cost of replacing warped millwork.

Myth 4: “Stacking for Acclimation”

The Myth: To save space, contractors often stack boxes of flooring or lumber in a tight pile in the corner of a room and leave them there to “acclimate.”

The Truth: Airflow is essential for acclimation. A dense stack of cardboard boxes prevents air from reaching the material in the center of the pile. The boxes on the outside might acclimate, while the boxes in the middle remain at their original moisture content. When installed, this results in a floor with mixed moisture levels, leading to uneven expansion and gapping.

- Best Practice: Materials must be “stickered” (stacked with spacers) or boxes must be cross-stacked to allow air circulation around the entire surface area of the packaging.

Myth 5: “New Homes Are Dry”

The Myth: Buyers of new construction in developments like FishHawk Ranch or South Fork often assume that because a house is brand new, it is “clean and dry.” The Truth: A new home is often the wettest it will ever be. A standard 2,000-square-foot home releases thousands of gallons of water during the first year of its life as concrete slabs cure, drywall compound dries, paint sets, and lumber stabilizes. If the builder “rushed” the closing—a common complaint in high-demand markets like Riverview—that moisture is trapped inside the building envelope. Installing moisture-sensitive finishes over a “green” slab or damp framing is a recipe for disaster.

3: The Role of the HVAC System in Material Preservation

In Florida, the Air Conditioning system is not a luxury; it is a life-support system for the building structure. It performs two distinct functions that must be balanced to protect materials: Sensible Cooling (temperature reduction) and Latent Cooling (moisture removal).

3.1 The Mechanics of Dehumidification

The standard residential air conditioner dehumidifies by accident of design. When warm, humid indoor air passes over the cold evaporator coil in the air handler, the temperature of the air drops below its “dew point.” Water vapor condenses into liquid water on the metal fins of the coil, drips into a condensate pan, and drains away outside the home.

Crucially, this process only occurs when the compressor is running. If the system is not running, no moisture is being removed. In fact, if the fan is left in the “ON” position while the compressor is off, the moving air can re-evaporate the moisture sitting on the wet coil and blow it back into the house, spiking humidity levels.

3.2 The Scourge of “Short Cycling”

A common issue in Florida tract homes and poorly designed renovations is “oversizing.” Builders or HVAC contractors, fearing customer complaints about the house not getting cool enough, often install an AC unit that is too powerful for the square footage (e.g., a 5-ton unit for a 1,600 sq. ft. home).

- The Consequence: The massive unit cools the air temperature to the thermostat setting (say, 74°F) in just 5 or 10 minutes. The thermostat, sensing the target temperature has been reached, shuts the system off.

- The Failure: Ten minutes is not enough time to remove significant moisture. The coil does not get wet enough for long enough to drain the water effectively. The result is a house that is cold but “clammy”—high relative humidity at low temperatures.

- Impact on Materials: This cold, damp air increases the EMC of materials. Floors may cup even though the thermostat says it is 72°F, because the Relative Humidity remains at 65% or 70%, keeping the wood swollen.

3.3 Advanced Control: “Overcool to Dehumidify”

Modern smart thermostats, which are increasingly common in Tampa Bay renovations and new builds, offer a feature specifically designed to combat short cycling and high humidity. This feature is often labeled “AC Overcool Max” (Ecobee) or “Cool to Dehumidify” (Honeywell/Nest).

- Mechanism: The homeowner sets a target humidity level (e.g., 55%). If the thermostat detects that the humidity is higher than this target, it will force the AC to continue running even after the temperature target is met, usually by up to 3 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Benefit: This extends the run time, forcing more air over the coils and extracting more water. It sacrifices a small amount of thermal precision (the room gets slightly colder than set) for the sake of dryness, which is vastly beneficial for material stability and indoor air quality.

- Implementation: For this to work, the thermostat must be correctly wired and configured. Many systems are installed with these features disabled by default. Enabling them is often the cheapest way to solve a humidity problem.

3.4 Variable Speed Systems

The ultimate solution for Florida humidity is the variable speed (or inverter-driven) AC system. Unlike a standard “single-stage” unit that is either 100% ON or 100% OFF, a variable speed unit can run at 30% or 40% capacity for hours at a time.

- Material Benefit: By running continuously at a low speed, the system keeps the evaporator coil cold and wet constantly, stripping massive amounts of moisture from the air without overcooling the house. This maintains a steady, low EMC that is ideal for hardwood floors and cabinetry.

4: Deep Dive – Flooring Failures and Solutions

Flooring is the most obvious and expensive victim of acclimation failures because it occupies the largest surface area of the home. In Florida, the two primary enemies are Cupping and Crowning.

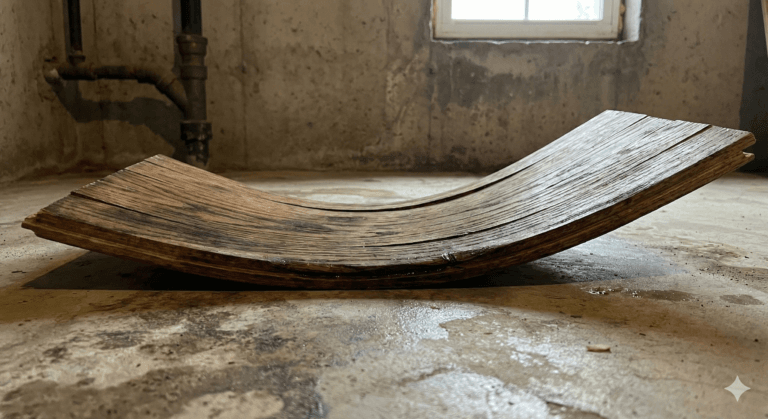

4.1 Cupping: The “Washboard” Effect

Visual: The edges of the board are higher than the center. When light hits the floor, it looks like a washboard or a series of small waves. Cause: Moisture imbalance where the bottom of the board is wetter than the top.

- Mechanism: The bottom of the board absorbs moisture from the subfloor. This causes the wood fibers on the bottom to expand. Since the boards are jammed tightly together, they cannot expand sideways. The path of least resistance is for the edges to curl upward.

- Common Florida Scenario: This frequently happens when wood flooring is installed over a concrete slab that was not properly tested for moisture. New slabs in Riverview can take months to cure. If a moisture barrier is insufficient or missing, vapor migrates from the damp earth, through the concrete, and into the bottom of the wood.

- HVAC Connection: Cupping also occurs if the AC is running powerfully (drying the top of the board) but the subfloor remains wet or humid due to a crawlspace issue or slab leak. The differential between the dry top and wet bottom creates the cup.

4.2 Crowning: The Convex Bump

Visual: The center of the board is higher than the edges. Cause: Moisture imbalance where the top of the board is wetter than the bottom, OR improper repair of cupping.

- Mechanism: The top of the board absorbs moisture (perhaps from mopping with water, a liquid spill, or extremely high room humidity) and expands while the bottom remains dry.

- The “Repair” Mistake: Often, a homeowner sees cupping (raised edges) and panics. They immediately call a flooring contractor to sand the floor flat. The sander grinds down the high edges. Later, when the moisture issue is resolved and the floor finally dries out, the cupping relaxes. The edges (which were sanded down) sink lower than the center, creating a permanent crown.

- Lesson: Never sand a cupped floor until the moisture issue is resolved and the wood has returned to equilibrium. This process can take months.

4.3 The Danger of Buckling

Buckling is the most extreme and catastrophic failure. The wood expands so significantly that it detaches from the subfloor, lifting several inches into the air. This is a structural failure, usually caused by flooding (pipe burst) or a complete lack of acclimation (e.g., installing dry wood in a very humid house with no expansion gaps left at the walls). Unlike cupping, buckling usually requires the total replacement of the floor.

4.4 Acclimation Best Practices for Flooring

To prevent these failures, a rigorous protocol must be followed:

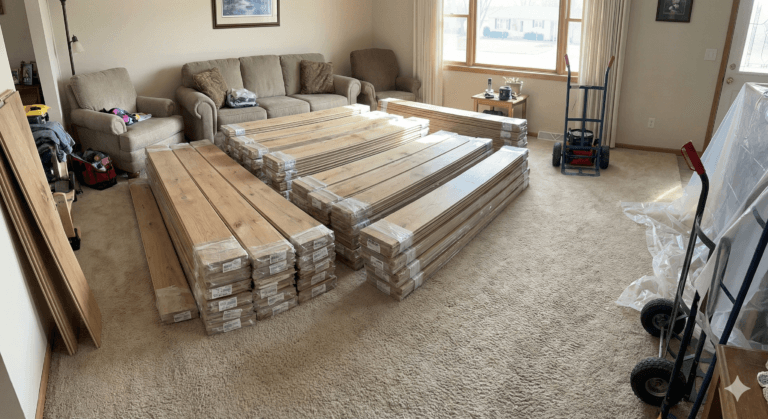

- HVAC Pre-Conditioning: The home must be at “living conditions” (75°F, 45-55% RH) for at least 5 days before the wood is even delivered. The AC must be fully operational.

- Delivery and Storage: The wood must be stored in the room where it will be installed. It cannot be stored in the garage, on a lanai, or in a non-air-conditioned room.

- The Moisture Meter Test: This is the non-negotiable step. The installer must measure the moisture content of the subfloor (concrete or plywood) and the new flooring using a calibrated meter.

- The Rule: For solid strip flooring (less than 3″ wide), the difference between the subfloor and the wood should be no more than 4%. For wide plank flooring (3″ or wider), the difference should be no more than 2%.

- If the gap is wider: You wait. You do not install. You continue to condition the space until the numbers align.

5: Deep Dive – Cabinetry and Millwork

Kitchen renovations are high-stakes projects, often costing tens of thousands of dollars. In Florida, the humid climate attacks the finishes of fine cabinetry, leading to aesthetic defects that can appear days or weeks after installation.

5.1 “Blooming” or “Blushing” of Finishes

Visual: A milky, white haze or cloudiness that appears in the clear coat or paint of the cabinets, often obscuring the wood grain or changing the paint color. Cause: High humidity during application or curing. Mechanism: Most high-end cabinet finishes (lacquer, conversion varnish, solvent-based paints) rely on solvents evaporating to cure the film. If the ambient humidity is high (above 70%), moisture from the air becomes trapped in the film as the solvents flash off. This trapped moisture creates microscopic voids that scatter light, appearing white to the eye. Prevention:

- Painters and cabinet finishers in Florida must use “retarders” (chemical additives that slow the drying process) to allow moisture to escape before the film hardens.

- Climate control must be active during the finishing and curing process. Applying high-end finishes in a house with the AC turned off is a guarantee of failure.

5.2 The “Sticky Door” Syndrome

Wood expands across the grain. A cabinet door frame made of solid maple will widen in high humidity.

- The Issue: If cabinets are installed in a non-acclimated house (HVAC off), and the installers adjust the doors to have tight, perfect “reveals” (the gaps between doors), the doors are set for failure. When the humidity rises, the wood swells, and the doors will bind (rub against each other), potentially chipping the expensive finish. Conversely, if installed in high humidity, they will shrink when the AC dries the house, leaving unsightly large gaps.

- The “Floating” Panel: Traditional raised-panel doors are designed with a center panel that “floats” in grooves to allow for movement. A common DIY mistake is painting these doors and bridging the gap between the panel and the frame with thick paint or caulk. When the panel naturally moves with humidity, it breaks this seal, creating a jagged, ugly crack line that homeowners often mistake for a defect in the cabinet.

5.3 The White Ring Phenomenon

Similar to blooming, water rings on wood tables or cabinets are caused by moisture penetrating the finish. In a humid home, finishes are softer and more permeable, making them more susceptible to this damage from drinking glasses or spills. The “white” color is actually light refracting off the water trapped beneath the finish. Remediation often involves using heat or alcohol to draw the moisture out, but prevention via humidity control is far superior.

6: Deep Dive – Drywall and Structural Shifts

Drywall is often considered a static background material, but it is highly sensitive to the cycling of temperature and humidity, primarily because it is attached to wood framing that is constantly moving.

6.1 Nail Pops and Screw Pops

Visual: Small, round bumps or crescent-shaped cracks in the wall paint, usually appearing in a vertical line spaced 16 inches apart. Cause: Lumber shrinkage. Mechanism: The wood studs behind the drywall have a moisture content. If a home is framed during the humid Florida summer and then sealed and air-conditioned, the studs dry out and shrink. As the wood shrinks away from the back of the drywall, the fastener (screw or nail) stays with the drywall but loses its tight grip on the wood, or the wood pulls back leaving the fastener head protruding slightly against the paint. Acclimation Connection: This is why builders often advise homeowners to wait to repair nail pops until the end of the first year (the “11-month warranty walk”). The house needs to go through a full cycle of seasons and drying to stabilize. Repairing them too early often leads to them popping again.

6.2 Truss Uplift

In winter, even in Florida, the bottom chord of a roof truss (which is buried in insulation and stays warm) experiences a different environment than the top chords (which are in the attic and get cold and damp). This differential causes the truss to arch upward, pulling the ceiling drywall away from the wall plates. This creates a crack at the corner where the wall meets the ceiling. This is often mistaken for foundation settlement but is purely a humidity/temperature acclimation issue known as “truss uplift”.

6.3 Mold Behind Baseboards

In new construction, if the drywall was installed near a wet slab or if the AC was run too cold too early, condensation can form behind the baseboards. Since vinyl baseboards or heavily painted wood trap moisture, mold can grow on the paper facing of the drywall. This is increasingly common in “tight” energy-efficient homes that do not manage latent moisture effectively.

7: New Construction Nightmares (A Florida Special)

The Tampa Bay area, particularly rapidly expanding suburbs like Riverview, Wimauma, and Ruskin, has seen a surge in “production building.” This speed often comes at the cost of proper material acclimation.

7.1 The “Rushed” Slab

Concrete takes 28 days to reach full structural cure, but it can take months to release its excess moisture. In the rush to meet quarterly closing dates, builders often lay flooring over “green” (wet) concrete.

- The Evidence: Forums and complaints regarding builders like Mattamy Homes and others in the Riverview area frequently mention tile cracking and wood floor buckling within the first year.

- The Mechanism: The moisture from the slab has nowhere to go but up. If the flooring is impermeable (like porcelain tile), the moisture pressure attacks the grout or the thin-set bond. If it is permeable (wood), it enters the wood, causing cupping.

- The Vapor Barrier Failure: A vapor barrier (thick plastic sheet) under the slab is essential. If this was punctured during construction (a common occurrence when workers walk on it before pouring concrete), the house has a permanent “leak” from the ground up, allowing infinite ground moisture to enter the slab.

7.2 The “Mold in New Construction” Scandal

Recent investigations in the Tampa area have highlighted new homes with mold growth behind baseboards, in attics, and on HVAC registers within months of closing.

- Cause: Building materials (lumber, drywall) were likely left exposed to rain during construction or installed wet. Once the house was sealed up (tight windows, stucco, spray foam insulation), the moisture was trapped inside. When the AC was turned on, it pulled the moisture out of the air, but the moisture inside the walls remained, feeding mold.

- Builder Warranty Issues: Many builder warranties specifically exclude “secondary damage” from moisture or limit coverage for mold, classifying it as a “homeowner maintenance” issue. This leaves homeowners with the bill for remediation.

8: Solutions and Technology

Homeowners are not helpless in the face of these challenges. Modern technology provides tools to monitor and control the indoor climate effectively.

8.1 Whole-Home Dehumidifiers

While the AC removes moisture, it only does so when cooling. In the “shoulder seasons” (spring and fall) or on cool, rainy days, the AC may not run enough to keep the house dry.

- The Solution: A dedicated whole-home dehumidifier (such as those from brands like Aprilaire or Santa Fe) ties directly into the home’s ductwork. It runs independently of the AC, removing moisture even when the temperature is comfortable.

- Capacity: For a standard Florida home, a unit removing 70–100 pints of water per day is typical.

- Efficiency: These units are far more efficient than portable dehumidifiers and distribute dry air evenly through the HVAC ducts.

8.2 Smart Thermostats: The Brain of the Operation

- Ecobee: This brand is highly favored for humidity control. Its “AC Overcool Max” feature allows the user to set a humidity threshold. If humidity is high, it uses the AC to drive it down, even if it means cooling the house below the set point.

- Honeywell T10 Pro: This thermostat supports “droop” control and can control a dedicated dehumidifier accessory. It also uses wireless room sensors to average humidity readings across the house, providing a more accurate picture of the home’s condition.

- Nest Learning Thermostat: The 4th Generation Nest can control dehumidifiers via its “star” terminal and offers “Cool to Dry” features, which function similarly to the Ecobee’s overcool feature.

8.3 The Humble Moisture Meter

For less than $50, a homeowner can own a pin-type or pinless moisture meter. This tool allows them to:

- Check walls for leaks before mold appears (crucial for 4-point inspections).

- Verify if wood flooring is ready to install by checking the subfloor and the plank.

- Provide data to a contractor who claims a substrate is “dry enough”.

9: Market Analysis – Central Florida Price Guide (2025/2026)

The following price table is based on current market rates in the Tampa/Riverview/Brandon area for services and products related to acclimation, humidity control, and remediation. These estimates reflect the localized labor market and material availability.

Table 1: Estimated Costs for Humidity Control & HVAC Services (Central Florida)

| Service / Product | Description | Estimated Price Range | Notes |

| HVAC Tune-Up | Seasonal inspection, coil check, drain line flush. | $49 – $159 | Lower end ($49-$79) are usually “new customer” specials. Standard maintenance is ~$129. |

| AC Repair (Minor) | Capacitor, contactor, or sensor replacement. | $150 – $650 | Includes diagnostic fee ($89-$100). |

| AC Repair (Major) | Compressor, coil replacement, or motor failure. | $750 – $2,500+ | Variable based on warranty status and parts availability. |

| Whole-Home Dehumidifier | Unit + Installation into existing HVAC. | $2,000 – $4,500 | Varies by capacity (70 vs 100 pint) and ductwork complexity. |

| Portable Dehumidifier | 50-pint standalone unit for single rooms. | $199 – $350 | Available at Lowe’s/Home Depot (brands: GE, Frigidaire, Hisense). |

| Moisture Meter | Handheld tool for wood/drywall. | $25 – $60 | General Tools or Klein Tools. “Pinless” models prevent wall damage. |

| Smart Thermostat | Device only (Ecobee Premium, Honeywell T10). | $180 – $300 | Installation adds ~$100-$150 if “C-wire” is missing. |

| Home Energy/Air Audit | Blower door test, thermal imaging, moisture map. | $350 – $500 | Some utility companies (TECO/Duke) offer rebates or simplified free audits. |

| 4-Point Inspection | Insurance inspection (HVAC, Roof, Elec, Plumb). | $100 – $150 | Often required for insurance renewal on older homes. |

| Mold Inspection | Air quality testing and surface sampling. | $250 – $500 | Includes lab fees for samples. |

Regional Insight: Riverview & FishHawk

- Service Demand: Due to the density of new construction in Riverview, HVAC companies are in high demand for warranty work. Wait times can be longer in summer.

- Hard Water Impact: The water quality in this region is hard. While humidifiers (adding moisture) are rarely needed, if used, they clog quickly without filtration.

- Salt Corrosion: Homes closer to the Alafia River or Tampa Bay need special anti-corrosion coatings on their outdoor AC units to prevent salt damage, which can lead to refrigerant leaks and loss of dehumidification capacity.

10: The Homeowner’s Action Plan

To protect your investment and ensure the longevity of your home’s materials, follow this protocol designed for the Florida climate.

10.1 Before a Renovation

- Stabilize the Environment: Run the HVAC at normal living temperatures (74-76°F) for at least 5 days before any materials are delivered.

- Order Early: Have flooring and cabinetry delivered to the job site (placed inside the AC-controlled space, not the garage) at least 3-5 days before installation.

- Verify: Ask your contractor to show you the moisture meter readings of the subfloor and the new material. Take a photo of the reading for your records.

10.2 During Renovation

- Keep AC On: Do not allow the contractor to turn off the AC for extended periods.

- Filter Defense: Buy a box of cheap, low-restriction filters (MERV 5-8). Change them every 2 days during dusty work. Do not use expensive HEPA filters during construction as they clog too fast and can freeze up the system due to airflow restriction.

- Supplemental Drying: If wet work (drywall mud, floor leveling compound) is heavy, run a portable dehumidifier to assist the AC in removing the excess load.

10.3 Daily Maintenance

- Monitor: Keep a simple hygrometer (humidity gauge) in the main living area. Target 45-55% RH.

- The 60% Red Line: If your humidity consistently stays above 60%, call an HVAC pro. You likely have an oversized unit, a duct leak, or a return air problem.

- Vacation Mode: If you are a snowbird or leaving for vacation, never turn the AC off. Set it to “Cool” at 78°F or 80°F. This is cool enough to dehumidify. Turning it off guarantees mold growth in Florida.

Conclusion

Material acclimation is not a myth; it is a fundamental law of physics that dictates the health of your home. In the unique climate of Central Florida, the air conditioner is the arbiter of this law. By understanding the relationship between moisture, temperature, and materials, homeowners can prevent the heartbreak of cupped floors and crumbling cabinets.

The “truth” is simple: Your home is a living ecosystem. The wood breathes, the drywall shifts, and the air conditioner acts as the lungs. Treat the system with respect—maintain it, monitor it, and let it do its job—and your home will weather the Florida humidity with grace.

Technical Appendix: Understanding the Science

Appendix A: The Psychrometric Chart Simplified

For those who want to understand the “Why,” we look to the Psychrometric Chart.

- Dew Point: The temperature at which air becomes 100% saturated and water condenses. In Florida summer, the dew point is often 75°F. This means if your AC cools a window surface to 74°F, it will sweat.

- Relative Humidity (RH): It is “relative” to temperature. Warmer air can hold more water.

- Scenario: It is 75°F and 50% RH inside.

- The Trap: If you turn the AC off and the house heats up to 85°F (with no new water added), the RH actually drops.

- The Reality: However, if you cool the air without removing water, RH rises. This is why an oversized AC that cools too fast causes high humidity—it drops the temperature (raising RH) but shuts off before draining the water (lowering absolute humidity).

Appendix B: Acclimation Cheat Sheet by Material

| Material | Acclimation Location | Timeframe (General) | The “Gold Standard” |

| Solid Hardwood | Installation Room | 3-7 Days | Within 2-4% Moisture Content of subfloor. |

| Engineered Wood | Installation Room | 48-72 Hours | Follow box instructions (often “keep sealed”). |

| Laminate / LVP | Installation Room | 24-48 Hours | Temperature balance is key for locking mechanisms. |

| Cabinetry | Installation Room | 2-3 Days | Do not store in garage. Install immediately after unpacking. |

| Drywall | On Site | 1-2 Days | Keep off the concrete floor (use spacers). |

Detailed Analysis: The Economics of Humidity Control

The Cost of Failure vs. The Cost of Prevention

A common objection from homeowners is the cost of running the AC or installing a dehumidifier. Let’s break down the economics for a Riverview home.

Scenario A: The “Thrifty” Approach

- Action: Homeowner turns AC off during the day or sets it to 82°F to save electricity.

- Result: Indoor humidity averages 65-70%.

- Energy Savings: ~$30/month.

- Consequences:

- Hardwood floors cup ($15,000 replacement cost).

- Cabinet joints swell and crack.

- Mold growth in closet leather goods (shoes/purses).

- Total Risk: >$20,000 in asset damage.

Scenario B: The “Climate Controlled” Approach

- Action: Homeowner keeps AC at 76°F with “Overcool to Dehumidify” enabled, or runs a whole-home dehumidifier.

- Result: Indoor humidity averages 45-50%.

- Energy Cost: +$20-$40/month.

- Consequences:

- Floors remain flat.

- Cabinets remain pristine.

- Air quality is higher (fewer dust mites/mold spores).

- Total Benefit: Preservation of home value.

ROI Calculation:

Spending $500/year in extra electricity to protect a $500,000 asset (the home) and $50,000 in finishes is a rational insurance premium. The “myths” of saving money by cutting AC run-time are financially illiterate in the context of the Florida climate.

Glossary of Terms

- Acclimation: The process of a material reaching moisture equilibrium with its environment.

- Cupping: Wood flooring warping where edges are higher than the center (moisture from below).

- Crowning: Wood flooring warping where the center is higher than edges (moisture from above).

- EMC (Equilibrium Moisture Content): The moisture percentage where wood neither gains nor loses water.

- Hygroscopic: A material that absorbs water from the air (wood, drywall, concrete).

- Latent Load: The energy needed to remove moisture from the air.

- Relative Humidity (RH): The amount of water vapor in the air relative to what it can hold at that temperature.

- Sensible Load: The energy needed to lower the air temperature.

- Short Cycling: When an AC runs for too short a time to dehumidify effectively.